What is a Category?

Category theory studies things, not through their structure, but the relationships they have with other things. I believe the point is that by abstracting over structure, we can see similarities from things we initially thought were unrelated, and carry knowledge from one over to the other.

This hasn’t worked for me at all - turns out that in order to carry knowledge over, you need to have knowledge to begin with. Who’d have thought.

What I’ve found myself enjoying is the weird perspective looking at things through the prism of relations brings; how it forces you to reframe the way you think.

So - category theory is about studying things and their relations. In order to do so, we need to have, well, things and relations. These things are called objects and arrows (or morphisms, depending on how clever we want to sound).

Objects and morphisms

An object is just some thing. We completely ignore its structure, and declare it to be a thing that can have relations with other things.

These relations are represented as morphisms, arrows between two objects. We’ll often write the morphism $f$ between objects $A$ and $B$ like this: $f: A \to B$, where $A$ is called the domain of $f$ and $B$ its codomain.

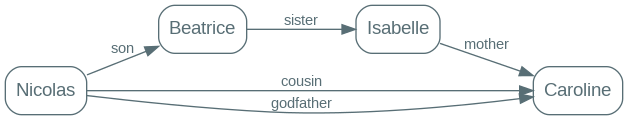

We could, for example, be interested in how people are related, but not at all care about other aspects, such as age, weight… Here’s a simple diagram representing the fact that I have a cousin named Caroline:

The only thing this diagram says about me is how I’m related to other people, completely ignoring any other aspect.

A very important thing to realise, and one which I of course entirely failed to realise for the longest time, is that morphisms that share a domain and codomain are not necessarily equivalent. For example, I’m both Caroline’s cousin and her godfather:

These two morphisms, $cousin$ and $godfather$, are not the same. They convey very different kinds of relationships. This will become important very soon when we start talking about diagrams that commute.

Having defined objects and morphisms - the data that composes a category - we need to talk about the structure of a category.

Identity

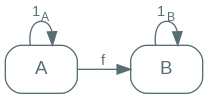

An object always has a relationship with itself: the fact that it is, well, itself. This is known as the identity morphism. We’ll write it $1_A$ for the identity of object $A$.

The identity morphism $1_A$ doesn’t actually tell us anything concrete about $A$, which translates to the fact that it leaves $A$ entirely untouched. While this might feel slightly less than useful, it quickly becomes very important when reasoning about things like uniqueness of some morphisms.

I’ll typically not draw the identity in diagrams, as every object always has it and things tend to get quite noisy quite quickly.

Composition

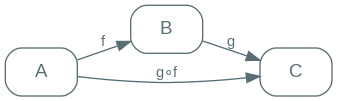

Morphisms compose: if $A$ is related to $B$, and $B$ related to $C$, then $A$ has some sort of relation with $C$.

Note the maybe surprising syntax for compound morphisms: $g \circ f$. This is the most common (but not the only) convention for writing such things, and one which I find extremely confusing.

You should read $\circ$ as of: $g \circ f$ is $g$ of $f$, meaning that you apply $g$ to the result of $f$. This feels like the wrong way around - I’d much rather read something like $f$ and then $g$, which makes reading and application order the same, but that’s not what most authors use, and as a result, a lot of vocabulary has been created that makes no sense with a different convention. Left-cancelable, for example, makes no sense if you’ve flipped the left and right operands.

Commutative diagrams

The Morphism Composition diagram has an important property that we’ll use quite a bit when reasoning about things: it commutes. This means that it does not matter which path you take between two objects, you’ll get the same result. In our specific diagram, going from $A$ to $C$ directly or by way of $B$ is the same thing.

This is not a property of all diagrams, and it’s very important to understand that as early as possible. I didn’t, which caused things to not make much sense for quite a while.

To hammer that point home, let’s take the cousin example maybe slightly further than it really should be taken.

Composing the $son$, $sister$ and $daughter$ morphisms yields $cousin$: both are stating the same things about my relationship with Caroline. That part of the diagram commutes.

On the other hand, the fact that I’m Caroline’s godfather is entirely unrelated to my being her cousin. Even though I can reach Caroline through both $mother \circ sister \circ son$ and $godfather$, the two morphisms describe different relations: that sub-diagram does not commute.

An important realisation (and one which I obviously failed to make for a long time) is that even diagrams with a single object might fail to commute - or, put another way, it’s perfectly possible for an object to have morphisms back to itself that aren’t $1$. I am, for example, both myself ($1_{Nicolas}$) and my own worst enemy ($worstenemy$). Those are two distinct relationships that happen to have the same domain and codomain.

Unitality

One important property of composition is how it behaves with the identity morphism.

The general idea goes like this: the identity morphism leaves objects untouched. It simply states that a thing is itself. For this reason, in order for us to be able to reason about things, err, reasonably, the identity morphism should change nothing when composed with another one.

In this diagram, $f \circ 1_A = f = 1_B \circ f$.

Associativity

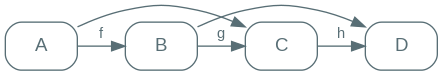

Finally, we want one last safeguard for our sanity: we do not want the order in which things compose to matter, because that way lies madness. This property (composition, not madness) is called associativity.

In this diagram, composition associativity states that $(h \circ g) \circ f = h \circ (g \circ f)$.

And this is really all there is to know about categories. Everything else can be derived from object, morphisms, and their properties.